The Constitutional Militia Movement

The Constitutional Militia Movement is often derided as a “far-right extremist group” by the usual suspects. Whether this is true or not is largely a matter of perception. However, what is undeniable is that the militia movement is profoundly American, as has been seen throughout our history of the militia.

While we discussed in detail how the militia in the United States has been used to suppress rebellion, it’s worth noting the degree to which the militia – the armed bodies of men who have made up the bulk of the American population until recent history – have also been a force of resistance against the state power which ultimately suppressed them. There are several examples of this, including the Revolution of 1800, the Dorr Rebellion and, more recently, the American Liberty League, to say nothing of the aforementioned black Civil Rights Movement gun clubs. In this sense, a Constitutional Militia Movement is no less American than a Free Speech Movement, and certainly more American than a movement championing the separation of church and state.

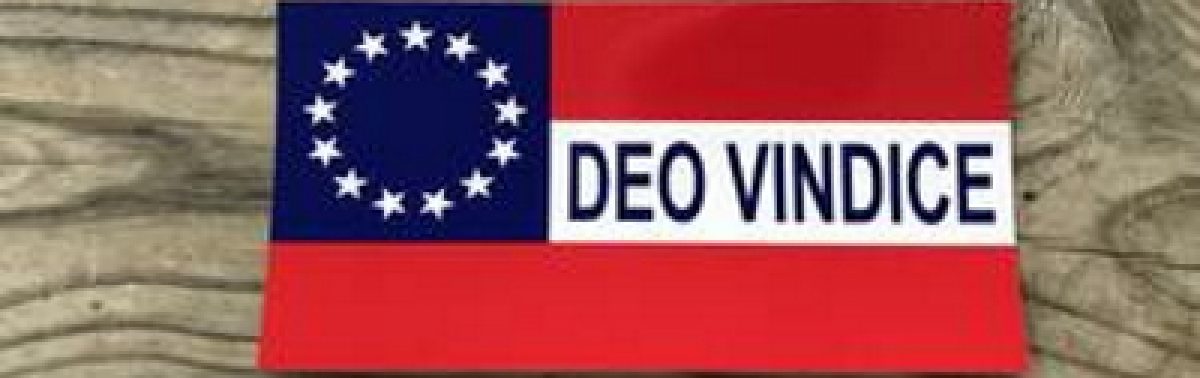

The origins of the modern militia movement in the United States are shady. Some date it back to 1958, but this is unfair and imprecise – the date is picked because of a militia formed by the Christian Identity movement. Indeed, much of the information about the history of the Constitutional Militia Movement in the United States is difficult to tease out, because it’s primarily documented by the movement’s enemies at self-styled “hate group” watches like the SPLC and the ADL or left-wing media like Vox and Mother Jones.

One thing is certain: The militia movement really started kicking off after the Ruby Ridge massacre where Randy Weaver’s son, wife and (of course) dog, were all shot down by federal agents on Weaver’s property. While the Weaver case has some nuance, it’s worth noting that the only thing Weaver was ever convicted of was failing to appear in court at a time when he didn’t know he was supposed to appear. Gun-owning patriots were, naturally, put aback by this. Combined with the Waco siege, where 76 men, women and children were burned alive, a new militancy in the nascent militia movement was inspired.

This is when groups such as the Michigan Militia, who allegedly had ties with Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, began to crop up. Indeed, there is a veritable rogue’s gallery of militias and militia members who were arrested, prosecuted and imprisoned for a litany of crimes. The degree to which these are legitimate charges and to what degree they are entrapment is anyone’s guess.

But there’s a whole other side to the militia movement. Militias such as the Missouri Citizens Militia, the Missouri Militia, the Ohio Defense Force and the Pennsylvania Military Reserve primarily see their mission as supporting the common defense in the event of an emergency. While it’s likely that individual members might be skeptical of, or even hostile toward, federal power, they’re not planning armed insurrections or even waiting for the right moment to do so. They see themselves as the successor of the organized militias of old. And while they might not realize it, this makes them more than a little like the militias raised to put down the Dorr Rebellion and other civil disturbances attacking federal power.

The two largest militia groups active today (though, of course, actual member numbers can be difficult to ascertain for obvious reasons) are probably the Oath Keepers and the 3 Percenters. The former’s membership is restricted to current and former military, peace officers and first responders. The Oath Keepers were involved in patrolling Ferguson, Missouri, during the rioting there in 2014 and 2015. They were positioned on rooftops around the city and ignored a police order to cease and desist. When Kim Davis refused to issue marriage licenses to homosexual couples, the Oath Keepers stated that they would prevent local police from arresting her a second time. Her legal team reached out to politely but firmly decline the offer.

The Bundy Ranch Standoff

Both groups were present at the Bundy Ranch standoff as well as the Occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. The Bundy Ranch standoff was one episode in a 25-year legal odyssey the Bundys waged against the Bureau of Land Management. The background of this is complicated, but the gist is that the BLM claimed Cliven Bundy owed them over $1 million in grazing fees, while Bundy claimed that he did not. On March 27, 2014, nearly 150,000 acres of land were closed for the collection of trespassing cattle. On April 12, 2014, protesters, some of whom were armed, confronted a BLM official. Sheriff Doug Gillespie negotiated a settlement with Bundy and then-BLM director Neil Kornze.

The standoff is interesting from the perspective of militia history because it features not only the unorganized militia (Bundy and his men), but also several organized militias, albeit not those explicitly under the command of the federal government, the Constitutional status of which would be a grey area anyhow. The Oath Keepers, 3 Percenters, the White Mountain Militia and the Praetorian Guard were all on the scene of the standoff.

The Occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge

Several of these figures showed up not much later in the Occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, a 40-day standoff (again) over the proper role of the federal government with regard to large tracts of land. The central character this time was Ammon Bundy, son of Cliven. The 3 Percenters also made an appearance, but did not stay for the duration of the standoff.

In each case, while the particulars of what was and was not legal about the Bundy’s relationship to the land and the BLM is, to some degree, in the eye of the beholder, what is not is that the Bundy and militia resistance worked, at least temporarily, in favor of the Bundys as a check on federal power.

This harks back to the original, revolutionary origins of the militia. The militia has existed for a number of purposes and has exercised a number of roles over the years. But at its core, it’s a bulwark of the power of the country against the power of the state.

Militias under the control of the state largely acted not along racial lines, but economic ones. State militias were increasingly deployed against striking workers in labor disputes.

Militias under the control of the state largely acted not along racial lines, but economic ones. State militias were increasingly deployed against striking workers in labor disputes.